IN a light, airy rehearsal room under the eaves of Perth Theatre, a cast of 10 actors is hunkered down at the front of a low stage.

Sitting in the middle of the group is veteran actor Gerry Mulgrew. At the far end, another familiar face: Tam Dean Burn. Facing them, an open script in front of him, is Ian Brown, a former artistic director of Edinburgh’s Traverse Theatre but now returned to Scotland for the first time in a decade – and returned to the very theatre where he directed his first professional production.

The cast read some parts of the script in chorus, other parts singly. It’s only the second day of rehearsals, so there’s a faltering quality to their rendition and at the end of each passage Brown stops to air his thoughts. The actors fire back their own interpretations and at one point Brown mentions Lincoln In The Bardo, George Saunders’s Booker Prize winning novel in which Abraham Lincoln is visited by the voices of the dead as he grieves for his son over the course of a night. A few heads nod in recognition.

Sitting quietly beside Brown and making notes as he talks is Morna Young, a 35-year-old playwright from Burghead near Elgin. It’s her words the cast are reading and discussing and, though Lincoln In The Bardo may not be on her bookshelf, grief and bereavement are emotions she knows intimately. Taped up against a far wall of the rehearsal space are a series of large photographs which point to the reason why. They show men in orange waterproofs, images of trawlers, seascapes and other scenes from what Young calls simply “the fishing” – the dangerous, hardscrabble profession which has sustained and shaped Scottish coastal communities for centuries but which also caused the death of her father when she was just five years old.

It’s his story, as well as the stories of all those other Scottish fishermen who have died offshore and the families and communities left behind to cope which are central to her play, Lost At Sea. More broadly, it’s a re-telling in song and speech of the last 40 years of the Scottish fishing industry.

“I think everyone always has a story inside them that they want to tell and I suppose this is part of me growing up and beginning to wonder who my dad was,” Young tells me when we settle down to talk in the theatre’s café. “Also I’d never had the chance to properly grieve for him because I was so young. And there is something incredibly cathartic about writing.”

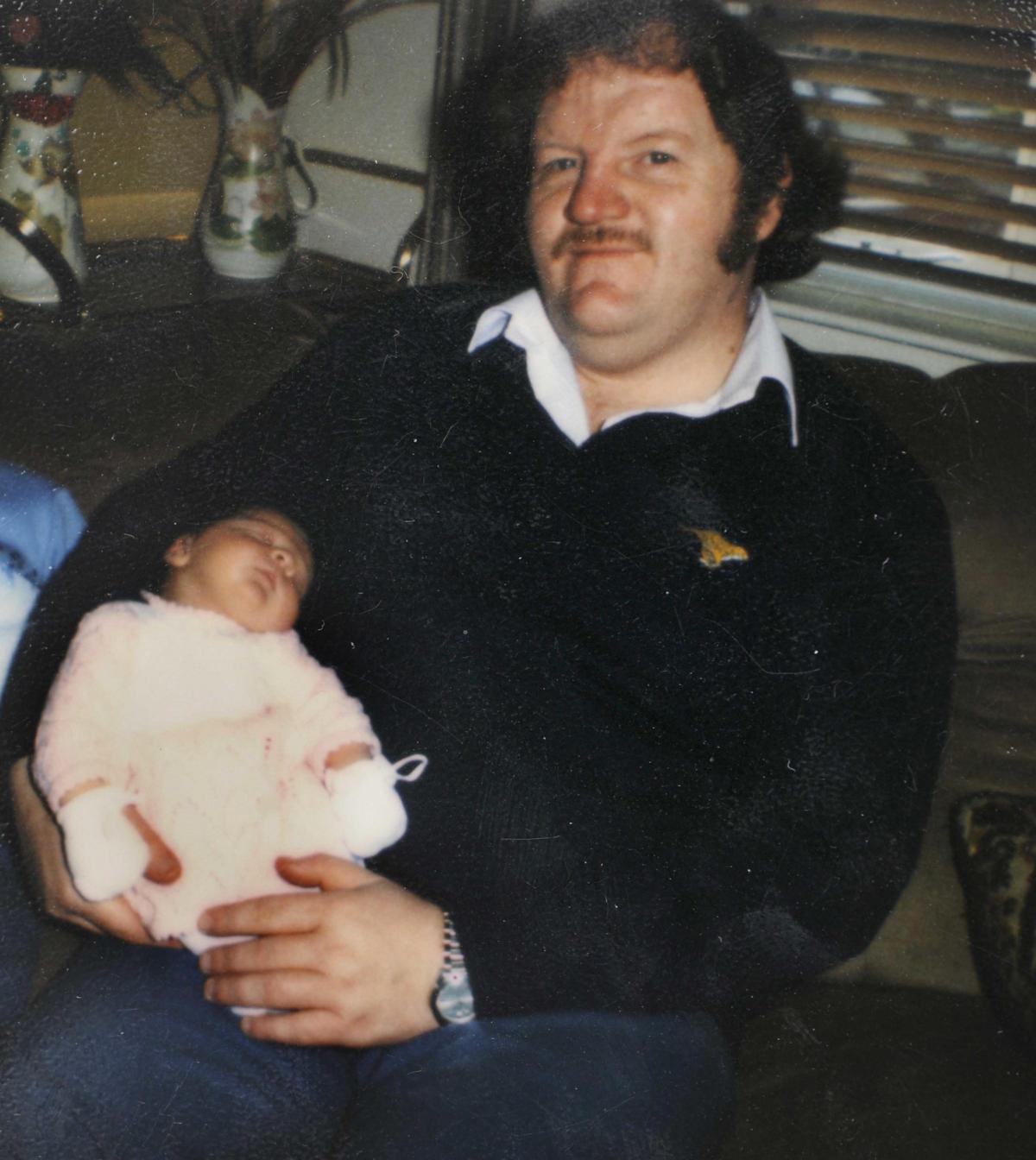

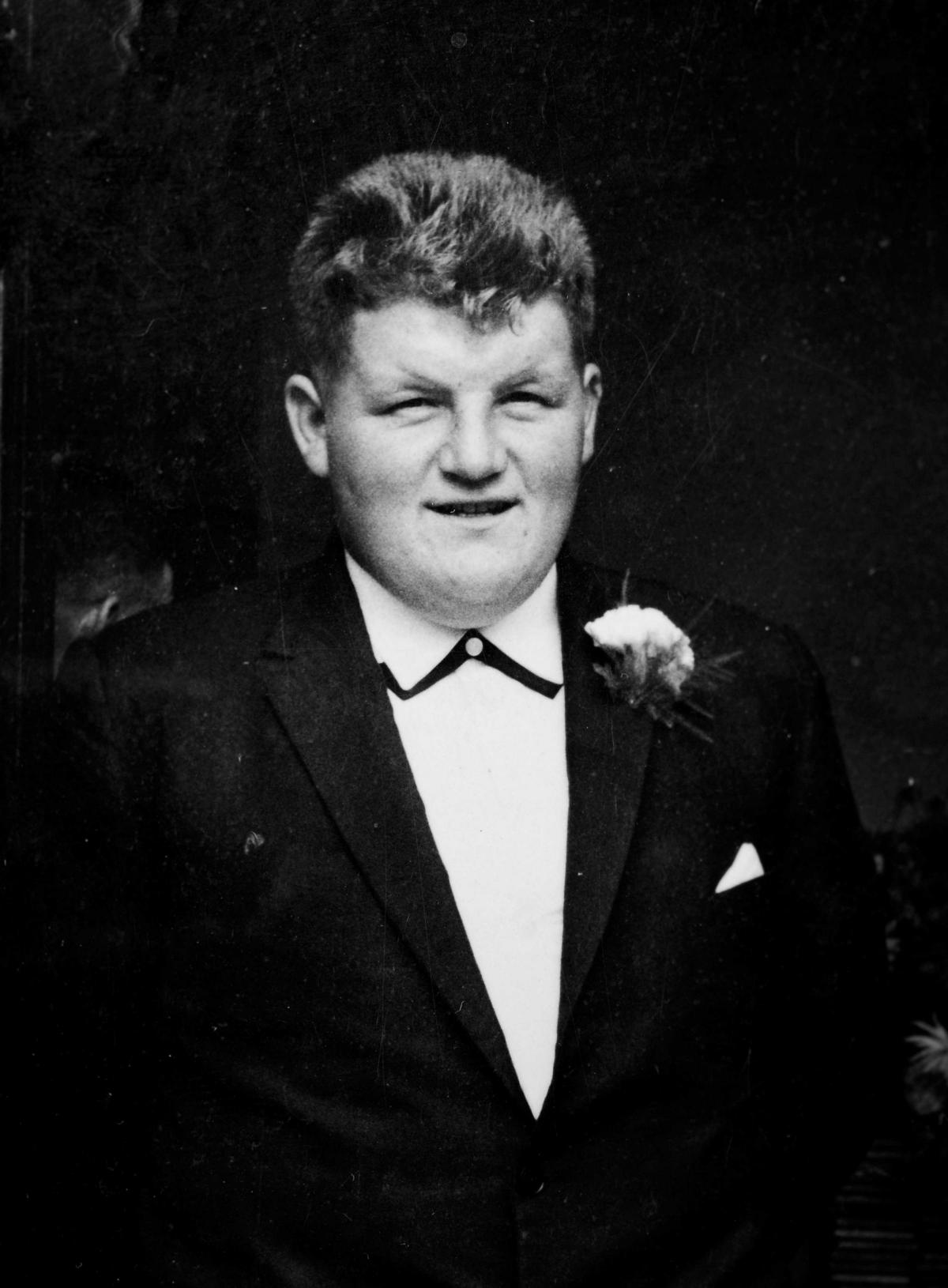

Her father, Donnie Young, was lost from the Ardent II in the Norwegian sector of the North Sea in April 1989, 30 years ago this month. He was 43, married and father to two children. His body was never found.

“I don’t really know what happened,” says Young. “He had gone overboard and was lost. I suppose the difficult thing about that is that when someone is lost at sea in that situation there’s no minute by minute account. That’s quite hard to comprehend.”

The family held a memorial service and a memorial stone was put in place. “So there’s a physical place we can go to and that does feel important. But not being able to have that body return home and have a funeral and to bury somebody, that’s really tough.”

YOUNG is from a family of fishermen. Her father’s brother also worked at sea, as did her great-grandfather. Her grandfather was a hiring skipper on whose boat many of the Burghead boys had their first taste of “the fishing”. But it was words rather than fish that Young chased, first as a journalist and then, when she turned her back on newspapers to audition for (and win) a place at London’s prestigious Royal Central School Of Speech And Drama, as an actor and musician.

What turned her into a budding playwright was a personal crisis. She finished a big theatre job in London and at the same time her relationship ended with the partner she was living with. “Everything changed. Suddenly I felt that all these things I had invested in, they’re nothing,” she says. “I lost a lot, very quickly. But it was a chance for me to think about what I wanted to do next.”

What she did next was move back home and turn her thoughts to the big one, the event that had always been there waiting to be faced and given meaning through words – the death of her father.

“Always in the back of my head I thought ‘I want to do this one day’ but I never felt quite ready to do it. That went on for a long, long time.” Returning home to Scotland meant that finally she was ready.

Young began work on Lost At Sea in 2011 and she did it by returning to her journalistic roots. She sat in pubs and houses, with a tape recorder in front of her, and talked to people from her village and from others along the coast. Her entry into the tight-knit fishing communities of the north-east was eased by the fact that she was of them herself. “Folk can say ‘Oh, you’re Donnie’s quine, you’re Daniel’s grand-daughter’. People know you.” By end of the process she had 50 hours of interviews and some of what’s in the play is taken verbatim from these.

The most personal aspect of the story-gathering project was simply to learn more about the father she never knew – or to “collect memories”, as she puts it.

“I do remember one of the fishermen saying to me: ‘You’ve started something here. We haven’t talked about these stories for years and now we’re all back in the pub sitting reminiscing again about the times we had’. I suppose a lot of people, because they were so fond of my dad, were very willing to tell stories about him.”

The more practical side was simply about information gathering. How do you use words, music, song and movement to re-create the working life of a fisherman and the rolling action of a boat, and make it all believable and visceral? She needed to know.

“It was about filling in gaps,” she says. “I had the personal experience of being a fisherman’s daughter but I didn’t know about the workings of a boat, I didn’t know the political side, I didn’t know anything about how the system worked day to day. So I was asking some very basic questions as well, sort of fishing for dummies. And they were very kind about that.”

Young even went to sea. She couldn’t find anybody who would take her on a trawler, which typically leaves port for a week or so continuous fishing, but she did do a couple of 15 hour stints on prawn boats. What was it like?

“Hard,” she laughs. “The first boat I went on I said to them ‘Put me to work’ and actually for the first couple of hours the skipper was going ‘Aye, you can tell you’ve got salt blood!’. But suddenly the world turned upside down and I thought ‘That’s sea-sickness. That’s what they talk about’. But it’s so different. I just thought I can’t write about what this feels like if I haven’t experienced it. I had the voices of the fishermen I’d spoken to but it felt really important to me that I go out and actually do some work.”

BUT there’s more to it than that because by donning her waterproofs Young was also negotiating her own relationship with the sea. We talk about Scottish-based author Charlotte Runcie’s recently published book, Salt On Your Tongue, a personal memoir which touches on the same subject but which is also an examination of what the sea means to women more broadly. It’s a chewy topic. Boats are referred to as “she” yet to have a women on board one is considered unlucky. And it’s the wives, sisters, mothers and daughters of fishermen who are left on shore while the men sail away.

“The women and the children were as much at sea as the men were in many ways,” Young reflects. “When I think about my childhood, the sea is there, always … I think the relationship is complicated but I also know that when I go for long periods of time without being near the sea I feel so restless. I feel the need to go back to it.”

She’s aware of Runcie’s book but for her own research she drew heavily on Jane Nadel-Klein’s Fishing For Heritage: Modernity And Loss Along The Scottish Coast. Rare for a study of the fishing industry, it looks at the part gender plays.

“It’s really difficult to find out anything about the role of women in the fishing industry because very often it’s history as told by men about men. And the fishing industry, on face value, is men. People are often surprised that this play is written by a woman.”

In fact Young’s research, based in part on Nadel-Klein’s book, has shown that some fishing villages were highly matriarchal, as it was often the women who were in charge of the money. “If the men are away to sea and then back for a day and away again, it’s the women who are the presence, and they’re in charge of the purse strings.”

The women also gutted fish and many of them – Young’s own great-grandmother included – would even carry their husbands out to the boats to stop the men’s feet getting wet. For Young, then, gender is at the forefront of Lost At Sea, the four female cast members as integral to the story as the six men.

“I think there’s a very strong female voice in the play and that was really important to me because I don’t think you can show one side of the story without showing the other,” she says. “And that of course comes from my own perspective as a woman, and from growing up with these incredible, strong women. When I think about my aunties and folk like that, they’re fish gutters, manual labourers. They’re strong.”

Young even took Ian Brown to Burghead, pitching the director into the heart of a typical fishing community and giving him a first-hand taste of its vitality and strength: in this case a cup of tea and a natter with one of those aunties, an irrepressible character by all accounts.

WHEN the curtain goes up on the opening night of Lost At Sea later this month Perth Theatre can celebrate a world premiere. But since 2011 when Young started her interviews, the play has been fine-tuned through a series of rehearsed readings and work-in-progress outings. Luck played a part too. Young wrote the first draft in 2012 and in the same year had a fateful meeting with the influential Muriel Romanes, then artistic director of trailblazing theatre company Stellar Quines. It resulted in Romanes directing a rehearsed reading of the play in Lossiemouth in 2013. “Someone taking a chance on you like that is enormous,” says Young. “I owe a huge amount of this to Muriel sitting in that meeting going ‘I don’t see your voice very often’.”

That idea of “voice” and representation is one Young returns to several times. Hers is that of a working class Scottish woman and it’s one she feels isn’t heard enough in theatre. The presence in the rehearsal room of theatre-makers of the calibre of Tam Dean Burn, Gerry Mulgrew, Ian Brown and award-winning sound designer Pippa Murphy, who’s composing the music, is both proof of that lack but also an indication that it’s being redressed.

To Young’s mind, it isn’t rocket science. “We all tell stories through our own lenses,” she says. “That’s why when we talk about working class theatre I always say you just need to commission more working class writers. The play doesn’t have to be about a working class subject. If you have commissioned a working class writer, it just will be.”

A case in point is Young’s short play Aye, Elvis, a hit at last year’s Edinburgh Fringe and resurrected earlier this month for a run at Glasgow’s Oran Mor. It was inspired by a visit Young made to a Glasgow pub for a karaoke session with former River City actress Joyce Falconer. When Falconer sat down again after blazing through an Elvis Presley number, Young told her there was a play in what she had just witnessed. “She thought I was joking until I handed her a first draft”.

On the face of it, Aye, Elvis is just “a really silly story about a female, Doric, Elvis impersonator. But what’s really going on underneath that is an exploration of working class voices. It’s about gender. It’s about asking the question: who gets to have a dream?”

Perhaps unsurprisingly given its success, Young has been asked to work up Aye, Elvis into a full-length play to tour Scotland next year in a production backed by concert promoters Regular Music. Regular boss Mark Mackie is a fan of Young’s and produced its Edinburgh Fringe run.

But there’s something else connecting Aye, Elvis and Lost At Sea besides its exploration of identity, class and gender and that is their shared sense of loss. It has featured in a great deal of Young’s work to date because it’s central to who she is as a person. “When you lose someone when you’re really young, you’re confronted at a younger age with the bigger questions about life which thankfully most of us don’t have to deal with until a little bit later. But I grew up with that question of loss.”

It's not a question that has an answer, perhaps, but that doesn’t mean trying to find one is futile. On the contrary, it makes someone like Morna Young even more determined to put words in actors’ mouths and through them share stories which can ease grief, reflect on lives lost and illuminate lives lived.

Late in our conversation Young pauses for a moment, then says this: “A pal said to me recently ‘Do you think you’d be writing about the fishing if your dad hadn’t been lost at sea?’ I said: ‘I don’t think I’d be writing full stop’.

So from loss, some good can come. Maybe that’s the only answer there is.

Lost At Sea runs at Perth Theatre until May 4. It then tours to Dundee, Aberdeen, Greenock, Inverness, Edinburgh and Dumfries.

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here