THOUSANDS of Scottish students will begin attending university for the first time this month, part of a tradition stretching back to 1410, when Scotland’s first university, St Andrews, was founded.

Glasgow, Aberdeen, and Edinburgh followed over the next two centuries, and then more after Strathclyde University was established in 1964. But where did Scots go to study before their country had its own universities?

Oxford had the beginnings of a university by the 12th century, and Cambridge by the 13th. But the regular warfare between the English and the Scots after Edward I invaded Scotland in 1296 made England a much less attractive destination for Scottish students for the rest of the Middle Ages.

Instead, most went to mainland Europe, some to the Low Countries and Germany. But it was France that was the main destination. The so-called Auld Alliance between Scotland and France saw the two countries intermittently support each other with money and troops in their various conflicts with England but it also led to a transfer of people.

Paris was home to most Scots studying in France. A Scots College was founded there in the early 14th century. But other French universities also took on Scottish students, such as Avignon, and by 1336, the Scots at the University of Orleans had even formed their own association. Some Scots went further south, to Italy, particularly the University of Bologna, as well as those of Ferrara, Padua, Pavia, Perugia, and Rome.

READ MORE: Rishi Sunak says he would not rule out blackouts if he became PM

Baldred Bisset studied law at Bologna in the late 1200s, eventually graduating with a doctorate. He would later put this education to use in 1301, when he was one of three intellectuals chosen by the Scottish Government to appear before the Pope to argue against Edward I’s claims over Scotland and present the case for independence. Even after the foundation of Scotland’s four Ancient Universities in the 15th and 16th centuries, many Scots continued to study in Europe.

The German universities of Cologne, Heidelberg, and Louvain all had Scottish students from the 15th century. Cologne even had a Scottish rector in 1502, Thomas Liel, a theologian who endorsed the notorious witch-hunting manual, the Malleus Maleficarum.

John Craig, personal doctor of James VI, studied at Konigsberg, Wittenberg and Frankfurt before eventually returning to Scotland.

Some of these students returned to Scotland to share what they had learned on the Continent. William Cadzow studied at Bologna before joining Glasgow University as a professor in theology in 1507. Andrew Melville, a theologian and the Principal of the University of Glasgow from 1574-80, had studied in Paris, Poitiers, and Geneva before coming back to Scotland.

The international reputation he built led to many foreign scholars coming to study at Glasgow and St Andrews, where Melville became Principal of St Mary’s College in 1580 and Rector of the university in 1590. After falling out with James VI, Melville was imprisoned in the Tower of London. Upon his release, he returned to Europe, taking up a post at Sedan, France.

Cardinal David Beaton, archbishop of St Andrews and the last Scots cardinal before the Reformation, studied at Orleans in 1519 and continued to have ties with the country until his murder at St Andrews Castle in 1546. Beaton visited France repeatedly as an ambassador and was given a French bishopric in 1537.

The Protestant Patrick Hamilton studied at Paris and Marburg before he was burnt at the stake inSt Andrews in 1528 after being tried for heresy by James Beaton, the cardinal’s uncle and predecessor as archbishop.

In the early 16th century, some Protestant scholars left Scotland to escape religious persecution. One such man, John MacAlpine, emigrated in 1534 first to Germany and then Denmark, where he joined the University of Copenhagen and created a Danish Bible translation.

Similarly, once Protestants took power in Scotland in 1560, many Catholic Scots would go abroad to be trained as priests, studying at dedicated Scots Colleges in Rome, Salamanca in Spain, or Douai in France.

One of the more unusual careers led by a Scottish academic on the Continent was that of William MacDowell, who studied philosophy at St Andrews before becoming professor of philosophy at the new Groningen University in the Netherlands in 1614.

He also moonlighted as head of the city’s Scottish militia and even became president of the province’s council of war. He later served as an ambassador first for the Dutch and then for Britain.

Even after the Reformation, the universities of Franeker, Groningen, Leiden, and Utretcht in the Netherlands continued to attract many Scottish protestant students.

James Boswell, the biographer of Dr Samuel Johnson, studied law at Utretcht in the 1760s and began compiling a Scots dictionary before embarking on a tour of Germany and Switzerland, where he met the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Some Scottish universities established their own, often less than legitimate, connections with mainland Europe. St Andrews, often in need of money in the 18th century, took to selling mail order qualifications, even for subjects which it did not teach.

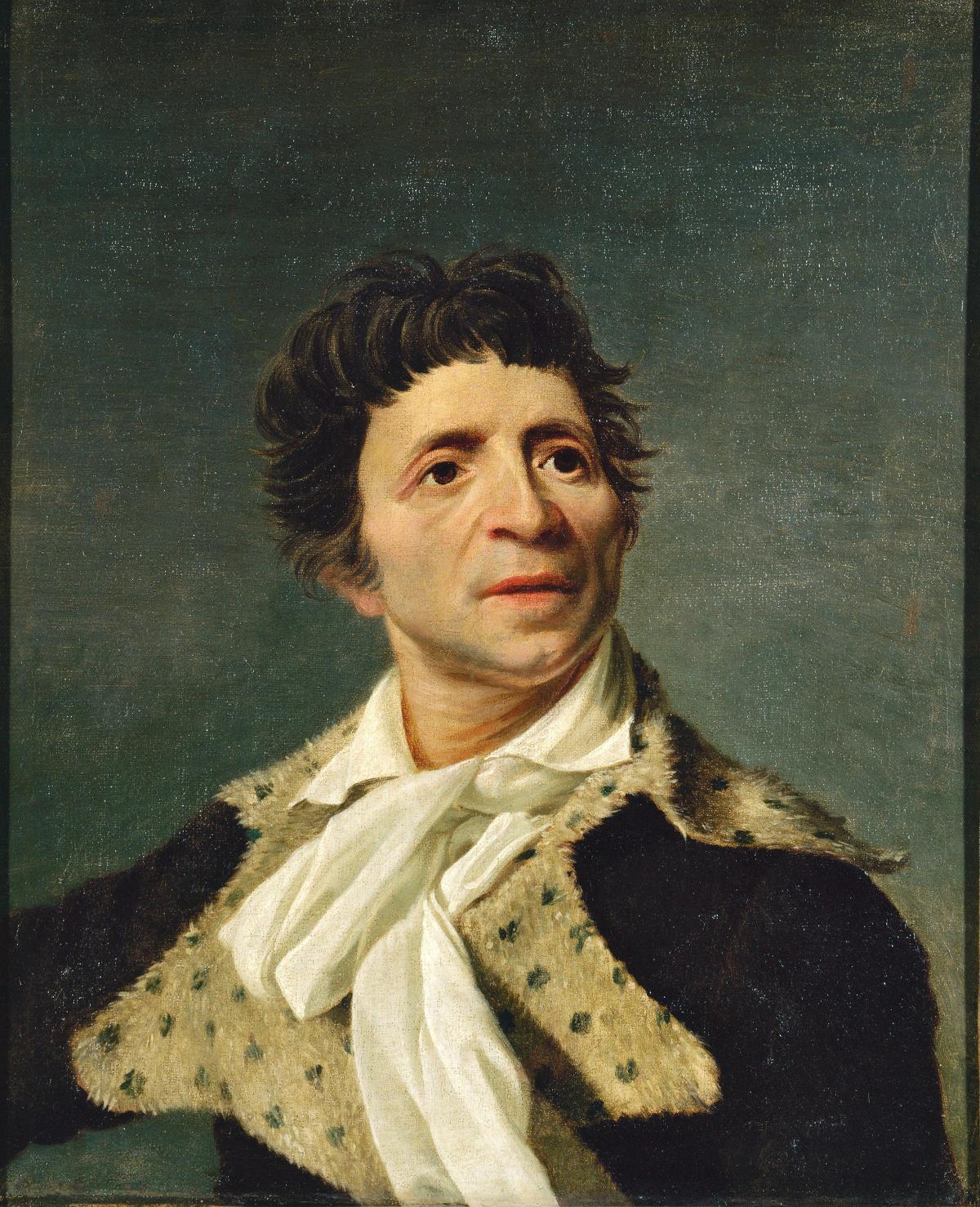

It even sold a doctorate of medicine to Jean-Paul Marat, the famous French revolutionary murdered in his bath in 1793, an event immortalised in Jacques-Louis David’s painting, The Death of Marat. Marat never visited St Andrews and the university didn’t even have a medical faculty at the time. Johnson is supposed to have remarked that St Andrews soon “grew rich by degrees”.

In the 17th century, and following the Act of Union in 1707, the numbers of Scottish students and academics studying on the Continent declined, as more and more chose to attend universities in Scotland or England instead.

Though some international connections persisted, not least through modern exchange programmes, sadly the UK’s withdrawal from Erasmus and other EU programmes has made these opportunities much more limited, threatening a centuries-old history of Scots studying at the universities of mainland Europe.

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel